Favorite Children’s Books of 2023 – The Marginalian

[ad_1]

Great children’s books are works of philosophy in disguise — gifts of wonder and consolation not only for the very young, but for the eternal child in each of us, conferring upon us what Maurice Sendak called “the pleasure of having your child self intact and alive and something to be proud of.” In the language of children — the language of curiosity and unselfconscious sincerity — they speak the most timeless truths to the truest parts of us by asking the simplest, deepest questions. Milan Kundera understood this when he wrote in The Unbearable Lightness of Being that “the only truly serious questions are ones that even a child can formulate” — questions without answers “that set the limits of human possibilities, describe the boundaries of human experience.” I read (and write) children’s books to broaden those boundaries, to deepen my questions, to magnify my sense of the possible.

After the year’s favorite books for grownups, here are a handful of children’s books I read and loved and wrote about this year that emanate these qualities of questioning, consolation, of wonder and self-transcendence.

BUNNY & TREE

We spend our lives yearning to be saved — from harm and heartache, from ourselves, from the inevitability of our oblivion. Religions have taught that a god saves us. Kierkegaard thought that we save ourselves. Baldwin believed that we save each other, if we are lucky. Ultimately, we don’t know, or only think we know, what saves us. But when it happens, we hold on to our saviors with the full force of gratitude and grace. In every true friendship, each is the other’s savior, over and over.

We spend our lives yearning to be saved — from harm and heartache, from ourselves, from the inevitability of our oblivion. Religions have taught that a god saves us. Kierkegaard thought that we save ourselves. Baldwin believed that we save each other, if we are lucky. Ultimately, we don’t know, or only think we know, what saves us. But when it happens, we hold on to our saviors with the full force of gratitude and grace. In every true friendship, each is the other’s savior, over and over.

That is what Hungarian artist Balint Zsako explores with great subtlety and sweetness in Bunny & Tree — a strange and wondrous wordless picture-book about a bunny saved from the archetypal hungry wolf by an unlikely savior — a sentient tree — and the unlikely friendship that blooms between them.

The story begins with Tree sprouting into life against Zsako’s exquisite watercolor skyscapes. Season after season, Tree grows in vigor and beauty — a “silent sentinel” to the world.

One day, an ancient drama unfolds beneath it — a ferocious fairy-tale wolf, black and fanged, pursues Bunny in a life-and-death chase that ends at the foot of Tree.

Suddenly, Tree’s crown shape-shifts into the silhouette of an enormous beast, menacing the wolf into retreat, then into a friendly face, cradling Bunny into safety.

So it is that Bunny and Tree enter the bonds of trust that undergird every true friendship. And, just like this, they decide to build a new life together in some faraway haven.

Carefully, lovingly, Bunny uproots Tree and they begin traversing day and night, mountain and valley, as Tree shape-shifts into just the right vehicle they need for each leg of their journey.

The story ends with a lovely wordless meditation on friendship, community, and the unstoppable ongoingness of life.

IN THE DARK

The mind is a camera obscura constantly trying to render an image of reality on the back wall of consciousness through the pinhole of awareness, its aperture narrowed by our selective attention, honed on our hopes and fears. In consequence, the projection we see inside the dark chamber is not raw reality but our hopes and fears magnified — a rendering not of the world as it is but as we are: frightened, confused, hopeful creatures trying to make sense of the mystery that enfolds us, the mystery that we are.

The mind is a camera obscura constantly trying to render an image of reality on the back wall of consciousness through the pinhole of awareness, its aperture narrowed by our selective attention, honed on our hopes and fears. In consequence, the projection we see inside the dark chamber is not raw reality but our hopes and fears magnified — a rendering not of the world as it is but as we are: frightened, confused, hopeful creatures trying to make sense of the mystery that enfolds us, the mystery that we are.

This reality-warping begins as the frights and fantasies of childhood, and evolves into the necessary illusions without which our lives would be unlivable. It permeates everything from our mythologies to our mathematics.

In the Dark (public library) by poet Kate Hoefler and artist Corinna Luyken brings that touching fundament of human nature to life with great levity and sweetness, radiating a reminder that if we are willing to walk through the darkness not with fear but with curiosity, we are saved by wonder.

Two girls venture cautiously into the dark forest, convinced that witches dwell there. Shadows fly across the sky that seem to confirm their conviction and deepen their fear.

But page by poetic page, as they keep walking and keep looking, they come to see that the shadows are not witches but “a wood full of birds.”

The birds, they realize, are kites flown from the hands of kindly strangers — people who have waded into the darkness to make their own light, the light of community and connection, the light of wonder.

AT THE DROP OF A CAT

That one mind can reach out from its lonely cave of bone and touch another, express its joys and sorrows to another — this is the great miracle of being alive together. The object of human communication is not the exchange of information but the exchange of understanding. If we are lucky enough, if we are attentive enough, communication then becomes a system for the transfer of tenderness. That we have invented so many forms of it — the language of words, the language of music, the language of flowers — is a testament to our elemental need for this exchange.

That one mind can reach out from its lonely cave of bone and touch another, express its joys and sorrows to another — this is the great miracle of being alive together. The object of human communication is not the exchange of information but the exchange of understanding. If we are lucky enough, if we are attentive enough, communication then becomes a system for the transfer of tenderness. That we have invented so many forms of it — the language of words, the language of music, the language of flowers — is a testament to our elemental need for this exchange.

A bright and immeasurably tender celebration of that need comes from French author Élise Fontenaille and Spanish artist Violeta Lópiz in their lovely collaboration At the Drop of a Cat (public library).

We meet a six-year-old boy just learning to read and write in his grandfather Luis’s house — a house Luis has built with his own hands, surrounded by a garden full of artichokes the size of heads and green beans climbing into the sky — a garden that “feels like a whole other world.”

Through the little boy’s unjudging eyes, in illustrations as textured and layered as a life well lived, a loving portrait of Luis emerges — his green thumb and the way he “speaks bird language,” his gifts for painting and cooking, his many tattoos, his thick Spanish accent and his charming misuse of idioms: He calls his grandson “the apple of his pie” and loves the expression “at the drop of a cat,” of which the little boy is so fond that he continues using it in school despite his teacher’s correction.

As the portrait unfolds, we realize that Luis misuses idioms because he has only ever heard them spoken, in a foreign tongue: When he was a little boy himself, having spent his childhood working in the fields, he fled war-torn Spain and “crossed mountains and hills and the countryside until he got to France.” He never went to school, never learned to write. Instead, he developed his own language of belonging — a living lexicon for feeling at home in the living world.

And that is how Luis communicates with his grandson — in the language of plants, in the language of paintings, in the language of love.

They draw together in the garden, forage in the meadow, and luxuriate in each other’s light as Luis plays his guitar under the cherry tree.

Radiating from the pages is the great tenderness that blooms between the young boy and the old man as they try to understand each other, to inhabit each other’s inner garden.

The day comes when the child reads a poem to his grandfather — he has finally learned to read and write, but he has also learned something else: that there are many languages of connection, each with its own dignity and delight, each an outstretched hand reaching for another.

YELLOW BUTTERFLY

In his little-known correspondence with Freud about war and human nature, Einstein observed that every great moral and spiritual leader in the history of our civilization has shared “the great goal of the internal and external liberation of man* from the evils of war” as Freud insisted that the more we understand human psychology, the more we can “deduce a formula for an indirect method of eliminating war.” In her timeless treatise on the building blocks of peace, the pioneering crystallographer and peace activist Kathleen Lonsdale located that formula in the moral education of our young — in teaching children, who are both the most vulnerable victims of war and the soldiers of the future, “at whatever cost not to give way to wrong or to co-operate in it.”

In his little-known correspondence with Freud about war and human nature, Einstein observed that every great moral and spiritual leader in the history of our civilization has shared “the great goal of the internal and external liberation of man* from the evils of war” as Freud insisted that the more we understand human psychology, the more we can “deduce a formula for an indirect method of eliminating war.” In her timeless treatise on the building blocks of peace, the pioneering crystallographer and peace activist Kathleen Lonsdale located that formula in the moral education of our young — in teaching children, who are both the most vulnerable victims of war and the soldiers of the future, “at whatever cost not to give way to wrong or to co-operate in it.”

My grandmother was a child in Bulgaria when the bombs of WWII rained down upon her and her three siblings, seeding into her marrow a lifetime of paralyzing anxiety that to this day never leaves her — not even in the safest of circumstances, not even with the sanest of her engineer’s reasoning. These scars that war leaves on the souls of children are a living testament to the great cellist Pablo Casals’s insistence that our primary motive force for ending violence should be “to make this world worthy of its children.”

How children survive the unsurvivable, how they keep the light inside aflame, is what Ukrainian artist Oleksandr Shatokhin explores in his stirring wordless story Yellow Butterfly (public library).

We enter a world of darkness and barbed wire, a world of which a frightened little girl is trying to make sense.

Running in terror from the bombs raining down upon her, she suddenly encounters a bright yellow butterfly.

As she goes on walking alongside the barbed wire — a haunting visual metaphor for how the terror of war constricts a life — the butterfly becomes her guide in the survival of the soul, gently flitting back and forth through the openings, its flight-path a promise of freedom, a promise of light.

Then another butterfly appears, and another, and another, until the constellation of them spreads across the land, alighting on the soldiers in the trenches, on the children at the playground, on the fallen bombs.

The butterflies multiply and multiply, becoming a great conflagration that illuminates the little girl’s face with the light of possibility, a great murmuration that wings her with hope.

So transformed, she gazes upon her war-torn homeland and pictures it sunlit with peace, blue-skied with freedom.

I TOUCHED THE SUN

“One discovers the light in darkness, that is what darkness is for; but everything in our lives depends on how we bear the light,” James Baldwin wrote in one of his finest, least known essays.

“One discovers the light in darkness, that is what darkness is for; but everything in our lives depends on how we bear the light,” James Baldwin wrote in one of his finest, least known essays.

In his exquisite memoir of the search for inner light, the blind resistance hero Jacques Lusseyran wrote in the same era: “Nothing in the world, not even what I saw inside myself with closed eyelids, was outside this great miracle of light.”

That search comes ablaze with uncommon tenderness in I Touched the Sun (public library) by musician and graphic novelist Leah Hayes — the story of a young boy’s quest to find and bear his own light.

One morning, warmed by the light of dawn, the boy awakes overcome by the desire to touch the sun.

His mother tells him it’s impossible — the sun is far too far. His father tells him it’s impossible — the sun is too hot to touch. His older brother, sipping soda by his bike, meets the quest with indifference.

And so the boy decides to go by himself.

He closes his eyes and launches into the sky. When he lands on the sun, he bends down to greet her and she embraces him hello with her great yellow arms.

We see the boy peeking from the sky onto a beach scene as the sun shows him where she works.

We see him admiring a bright flower as she shows him “what she’s made.”

She showed me things that took her years to grow…

…and things that only lasted seconds.

Carrying the story is the quiet conversation between the black-and-white simplicity of Hayes’s pencil and the incandescent richness of her crayons, emanating the candor of a child’s drawing and the refined subtlety of an artist’s lens on the world — a world of contrasts in the act of being made on the page, like a young life still unwritten, yet to be colored in with living.

Before the boy leaves, he asks the sun one simple, immense question: Where does her light come from?

From inside, she tells him, touching his heart.

Suddenly, a bright inner sun comes ablaze within him — the light he always carried, “not too hot, but just right,” now found.

The sun inside began to shine outward. It made me feel brilliant with light, like I could wake up the world with just my touch.

So illuminated, the boy feels ready to return home and embraces the sun goodbye before flying back down to Earth, where he finds his mother mesmerized by the stunning sunset aglow outside.

She doesn’t seem to notice anything has changed in him. Nor does his father as he carries the sleepy child up the stairs.

But looking out his bedroom window into the night sky, the boy knows, the boy feels that the light is always and already there.

WE ARE STARLINGS

Biking back to my rented cottage from CERN one autumn evening, having descended into the underworld of matter for a visit to the world’s largest high-energy particle collider, a sight stopped me up short on the shore of Lake Geneva: In the orange sky over the orange water, myriad particles were swarming in unison without colliding. Except they were not particles — they were birds. Thousands of them. A murmuration of starlings — swarm intelligence at its most majestic, emergence incarnate, a living reminder that the universe is “nothing but a vast, self-organizing, complex system, the emergent properties of which are… everything.”

Biking back to my rented cottage from CERN one autumn evening, having descended into the underworld of matter for a visit to the world’s largest high-energy particle collider, a sight stopped me up short on the shore of Lake Geneva: In the orange sky over the orange water, myriad particles were swarming in unison without colliding. Except they were not particles — they were birds. Thousands of them. A murmuration of starlings — swarm intelligence at its most majestic, emergence incarnate, a living reminder that the universe is “nothing but a vast, self-organizing, complex system, the emergent properties of which are… everything.”

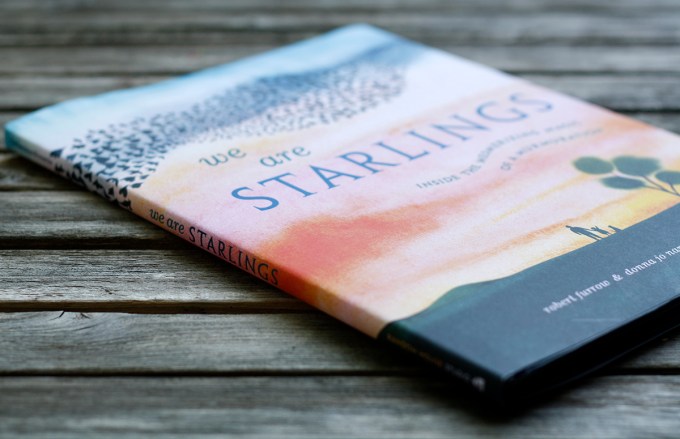

The majesty and mystery of murmurations come alive with uncommon beauty in We Are Starlings: Inside the Mesmerizing Magic of a Murmuration (public library) by writers Donna Jo Napoli and Robert Furrow, illustrated by artist Marc Martin, who also brought us the wondrous A Stone Is a Story.

As a murmuration of starlings takes flight against a breathtaking watercolor sky, the story is told from the perspective of the birds — an antidote to our anthropocentric view of the natural world, which Rachel Carson pioneered nearly a century ago with her revolutionary writings about the sea.

Soft yet striking, the illustrations play masterfully with our sense of scale — we zoom out and out from closeups of the flock to the full sweep of the murmuration, then back to the scale of the feathered particle that is the individual bird.

A four-page gatefold wings the book with a sense of the astonishing grandeur of these small, fragile creatures constellating something immense and powerful, greater than the sum of its parts — one of the living wonders of this Earth.

Couple We Are Starlings with the lovely animated poem “Murmuration,” then revisit other kindred illustrated celebrations of the natural world: The Forest, Dawn, What Is a River, and The Blue Hour.

BEAR IS NEVER ALONE

“One can never be alone enough to write,” Susan Sontag lamented in her diary. “Oh comforting solitude, how favorable thou art to original thought!” the founding father of neuroscience exulted in considering the ideal environment for creative breakthrough.

“One can never be alone enough to write,” Susan Sontag lamented in her diary. “Oh comforting solitude, how favorable thou art to original thought!” the founding father of neuroscience exulted in considering the ideal environment for creative breakthrough.

All creative people, however public or performative their work may be, yearn for that contemplative space where the mind quiets and the spirit quickens. The ongoing challenge of the creative life is how to balance the outward sharing of one’s gift with the inward stewardship of the soul from which that gift springs.

How to master that delicate balance is what Dutch author-illustrator duo Marc Veerkamp and Jeska Verstegen explore in Bear Is Never Alone (public library), translated by Laura Watkinson.

In the middle of the forest, Piano Bear is performing for a rapt and ravenous audience insatiable for his music.

As all the creatures’ delight in his gift for beautiful music metastasizes into a demand, Piano Bear begins yearning for stillness and solitude. But everywhere he turns, the other animals follow with their incessant incantation of “MORE!”

Finally, pushed to his limits, Piano Bear startles the forest with a great big roar of exasperation, then immediately curls up into a ball of shyness.

Just as he thinks he is at last alone, Piano Bear notices a quiet presence that has been there in the crowd all along — a lone zebra striped with her own gift: words.

As a token of gratitude for all the beautiful music she has been silently enjoying, the zebra offers to read Piano Bear a story. Cautious at first of another intrusion, he comes to see that there is great joy in a shared solitude — a testament to Rilke’s insistence that the highest task of a bond between two souls is for each to “stand guard over the solitude of the other.”

HOW THE SEA CAME TO BE

“Who has known the ocean? Neither you nor I, with our earth-bound senses,” Rachel Carson wrote in the pioneering 1937 essay that invited the human imagination into the science and splendor of the marine world for the first time — a world then more mysterious than the Moon, a world that makes of Earth the Pale Blue Dot that it is.

“Who has known the ocean? Neither you nor I, with our earth-bound senses,” Rachel Carson wrote in the pioneering 1937 essay that invited the human imagination into the science and splendor of the marine world for the first time — a world then more mysterious than the Moon, a world that makes of Earth the Pale Blue Dot that it is.

In the near-century since, we have made great strides in illuminating the wonderland of the sea — from the birth of sonar and the revelations of the first submersibles to our ongoing discoveries of astonishing sea creatures. And yet even so, we have only explored about a tenth of the world’s waters. The oceans, which comprise 99% of the living space on our planet and make it a world, remain largely a mystery — the mystery out of which we emerged to walk the land, to make books and mathematics, to invent sonar and love.

Author Jennifer Berne and artist Amanda Hall celebrate our footholds of knowledge amid the mystery in How the Sea Came to Be (And All the Creatures In It) (public library) — a singsong chronicle of how Earth went from roiling rock to living wonderland, pulsating with the elemental poetry of nature.

Volcanoes exploded from inside the Earth.

They blazed and they blasted and boomed.

And comets and asteroids crashed out of the sky,

icy and rocky they zoomed.Earth sizzled and simmered for millions of years.

It bubbled and burbled and hissed.

It raged and it rumbled, it thundered and boiled,

spewing lava and steamy hot mist.

And then the slow cooling and firming, the crumpling of mountains and valleys, the formation of the atmosphere, the first clouds and the first rain — pouring down “for days and for nights, for thousands of years,” giving birth to the sea, giving birth to life itself.

Then something amazing, unseen, and so new

appeared in the shining blue sea…

The teeniest, tiniest stirrings of life

came to be, in the sea, came to be.Though smaller than small, and adrift in the seas,

one became two became four.

For millions of years these first bits of life

became more, and then more, and then more.

This was the great explosion of adaptation and transformation, out of which eventually arose the tiniest plankton and the great blue whale, jellyfish that “move with a watery sigh” and fish that “look silvery when seen from below to disguise them as light from the sky,” the octopus (that wonder of consciousness) and the eel (that living enigma).

The story unfolds to trace the evolution of life from the ocean to the land, ending with a scene of children playing in the tide pool from which they came as the waves go on lapping at the shore of the ocean to which they will one day return.

THE LOST DROP

I remember when I first learned about the water cycle, about how it makes of our planet a living world and binds the fate of every molecule to that of every other. I remember feeling in my child-bones the profound interconnectedness of life as I realized I was breathing the breath of Aristotle and William Blake and Marie Curie, those exact molecules still lingering in the water vapor comprising the atmosphere that makes the whole world breathe — a living testament to Lynn Margulis’s observation that “the fact that we are connected through space and time shows that life is a unitary phenomenon.”

I remember when I first learned about the water cycle, about how it makes of our planet a living world and binds the fate of every molecule to that of every other. I remember feeling in my child-bones the profound interconnectedness of life as I realized I was breathing the breath of Aristotle and William Blake and Marie Curie, those exact molecules still lingering in the water vapor comprising the atmosphere that makes the whole world breathe — a living testament to Lynn Margulis’s observation that “the fact that we are connected through space and time shows that life is a unitary phenomenon.”

That wondrous interleaving of space, time, and being comes alive with uncommon sweetness in The Lost Drop (public library) by Grégoire Laforce, illustrated by Benjamin Flouw — a vibrant love letter to the water cycle as a portal to deep time and deep presence, and a subtle celebration of the ongoingness of life as a way to bear our mortal smallness in the great scheme of being.

The story, rendered with the charming feeling-tone of mid-century illustration, begins with a little drop named Flo, who falls from the sky and, upon hitting the ground, is seized with the existential question that pulsates beneath every life:

Who am I and where should I go?

She finds herself pulled by gravity down a slope and into a stream — the portion of the water cycle called runoff.

As she flows, she asks all the rocks and trees and animals nourished by the stream what her purpose might be, but they just nod and smile.

The stream pours into a lake full of prehistoric sea creatures, and still she goes on wondering about her fate. Then a waterfall leaps her into the air and plunges her into the dark depths, still and silent.

She screams her question into the silence as she drifts toward the surface, until a sudden surge of sunlight envelops her — the evaporation portion of the water cycle begins.

Flo grows smaller and smaller, then seems to become part of the light, almost vanishing into the air — “but not quite.”

Flo helped make the trees dance,

and united the breath of all living creatures,

and lifted wings into flight.

There is homecoming in the sky as the condensation part of the cycle returns Flo from vapor back to liquid, at last conferring meaning upon her existence as a unit of aliveness and a particle of time, four billion years old yet ever-new.

LITTLE BLACK HOLE

Right this minute, people are making plans, making promises and poems, while at the center of our galaxy a black hole with the mass of four billion suns screams its open-mouth kiss of oblivion. Someday it will swallow every atom that ever touched us and every datum we ever produced, swallow Euclid’s postulates and the Goldberg Variations, calculus and Leaves of Grass.

Right this minute, people are making plans, making promises and poems, while at the center of our galaxy a black hole with the mass of four billion suns screams its open-mouth kiss of oblivion. Someday it will swallow every atom that ever touched us and every datum we ever produced, swallow Euclid’s postulates and the Goldberg Variations, calculus and Leaves of Grass.

When black holes first emerged from the mathematics of relativity, Einstein himself wavered on whether or not they could be real — he struggled to imagine that nature could produce so menacing a thing, that spacetime could bend to such a monstrous extreme. And then it took us a mere century to hear with our immense prosthetic ear the sound of two black holes colliding to churn a gravitational wave, then to see with our telescopic eye an actual black hole in the cosmic wild. Here looms living proof of Richard Feynman’s insistence that “the imagination of nature is far, far greater than the imagination of man.”

With their cosmic drama and their dazzling science at the edge of the possible, black holes beckon the human imagination with myriad metaphors for our existential perplexities. One of them comes alive in Little Black Hole (public library), by

Radiolab producer Molly Webster and artist Alex Willmore — an uncommon meditation on how to live with the austere existential loneliness of knowing that everything and everyone we cherish can be taken away from us and is ultimately destined for oblivion, how to live with the looming loss that is the price of being fully alive.

The story’s central conceit draws on Stephen Hawking’s black hole information paradox — the combined intimation of relativity and quantum field theory that, even though not even light can escape from a black hole, bits of information can transcend its immense gravitational pull and break free in the form of what is known as Hawking radiation.

Tucked into the lyrical opening lines is a subtle vulpine allusion to The Little Prince, that most poetic of cosmic tales:

There once was a little black hole who loved everything in the universe.

The stars. The planets. The space rocks and the space fox. Even the flying astronauts.

The little black hole loved her friends.

One day, the little black hole befriends a star, but just as they are delighting in building a cosmic castle together, the star vanishes, her light nowhere to be seen.

Next, a comet swings by, but just as the little black hole grows giddy for a new friendship, the comet crumbles to cosmic dust and disappears.

So they come and they go, the planets and the asteroids, the fox and the astronauts, each new friend taken away as soon as they get close, leaving the little black hole baffled and bereaved.

Confused and disconsolate, the little black hole comes upon a big black hole replete with an elder’s wisdom, who illuminates the fundamental fact that to be a black hole means to swallow and annihilate anything and anyone who comes near.

And yet bits of information can escape from the belly of the black hole, bubbling back up as remnants of what was consumed. Out of Hawking’s legacy arises the story’s central metaphor for how to live with loss: Because, in poet Meghan O’Rourke’s lovely words, “the people we most love do become a physical part of us, ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created,” we can always bring them back up to the surface of our consciousness with the twin levers of memory and imagination.

This might seem like cold consolation for the infernal heat of loss. And yet it is no small gift that a cold cosmos kindled the warm glow of consciousness — this radiant faculty that makes it possible to love and to suffer, to imagine and to remember; this wonder that — like music, like love — didn’t have to exist.

[ad_2]

Source link