Requiem for a Forgotten West Texas Cow Town

[ad_1]

Bad, bawdy and bankable during its 1880s heyday, Colorado City blossomed as one of the Lone Star State’s major cattle towns, only to wilt away within the decade like a funeral wreath beneath the scorching west Texas sun. When the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway came to Colorado City in 1881, west Texas and eastern New Mexico Territory cattlemen and their herds followed, prompting an economic boom that made the community the last, if least remembered, of the great cow towns that dotted the American West between 1865 and ’90.

Perched on the banks of the Colorado River, the railhead at Colorado City was central to the development of the region, so much so that the town earned the moniker “Mother City of West Texas.” The community provided not only vice and nice for area ranch hands but also supplies and building materials for regional ranches and other nascent communities seeking prosperity and permanence in west Texas and the Texas Panhandle. The latter distinction would prove its undoing.

Settling a Boomtown

(Heart of West Texas Museum, Colorado City)

What started on Sept. 1, 1880, as A.W. Dunn’s 25-by-60-foot store with a dirt floor, plank walls and a canvas roof evolved into west Texas’ first boomtown. Colorado (as the settlement was known before opening a post office and proclaiming itself a city) developed an early reputation as the lustiest and roughest town between Fort Worth and El Paso. Though Dunn settled the site, the burgeoning city owed its decade of economic significance to financier Jay Gould, among the most unscrupulous and reviled business magnates of the 19th century.

Chartered by Congress in 1871 to extend from Marshall, Texas, to El Paso, where it would connect with the Southern Pacific, the T&P experienced financial difficulties in 1876 that halted construction at Fort Worth. For more than three years all work on the T&P stopped while Gould sought investors to revive the moribund project. Meanwhile, the Southern Pacific muscled its way eastward through El Paso and 92 miles farther to Sierra Blanca. Westward tracklaying on the T&P resumed on April 1, 1880, reached Colorado City on April 16, 1881, and finally linked up with the Southern Pacific at Sierra Blanca on Dec. 16, 1881.

Its riverside locale made Colorado City special among rival railheads along the route. Cattle can gulp down as many as 15 gallons of water each on hot days, and the Colorado River provided arriving herds plentiful, albeit brackish, water. Besides beeves, the community also shipped out sheep and wool, securing its place as a regional livestock hub.

When the T&P arrived, Colorado City had already grown to include 12 merchants, five saloons, three hotels, two livery stables, two wagon yards and a restaurant, plus three lawyers. By 1884 it boasted 75 merchants, 28 saloons, seven billiard halls, four hotels, four theaters, two banks, two livery stables, a 75-by-100-foot skating rink and a mule-drawn streetcar service that ran from downtown east to a 60-acre city park with a pavilion, beer garden, zoo and racetrack. Professionals hanging up their slates included 17 doctors, 12 lawyers, seven peddlers, three land agents, two photographers, two lightning rod salesmen and a dentist.

That same year English novelist Morley Roberts visited Texas—“the land of revolution and rude romance and pistol arbitration,” as he called it—to see his brother in Colorado City. “My impressions of the town and its people were favorable,” he wrote. “There were many men walking round the streets dressed in wide-brimmed hats, leather leggings with fringe adornments and long boots with large spurs rattling as they went. They were mostly tall and strong, and I noticed with interest the look of calm assurance about many of them, as if they had said to themselves: ‘I am a man, distinctly a man, nobody dares insult me; if anyone does, there will be a funeral—and not mine.’”

Locals seemed to carry fewer guns than Roberts, having read Bret Harte stories, had expected. But his brother soon disavowed him of that notion, revealing “that almost everybody in town carried revolvers concealed under his coattails or inside his waistcoat, and that people were occasionally shot in spite of the peaceful look of the place.”

In Reconstruction-era Texas state laws and local ordinances limited the carrying of weapons in public. A detail of Texas Rangers stationed in the area since 1877 often enforced those restrictions. But while the weapons may have been hidden, violence was all too painfully obvious at times.

Controversial Killings

Soon after the first T&P train rolled into town in April 1881, one snarky reporter quipped, “Colorado City has started out with a gross population of 250 cutthroats and gamblers.” Such hyperbole aside, ne’er-do-wells did inevitably follow the tracks.

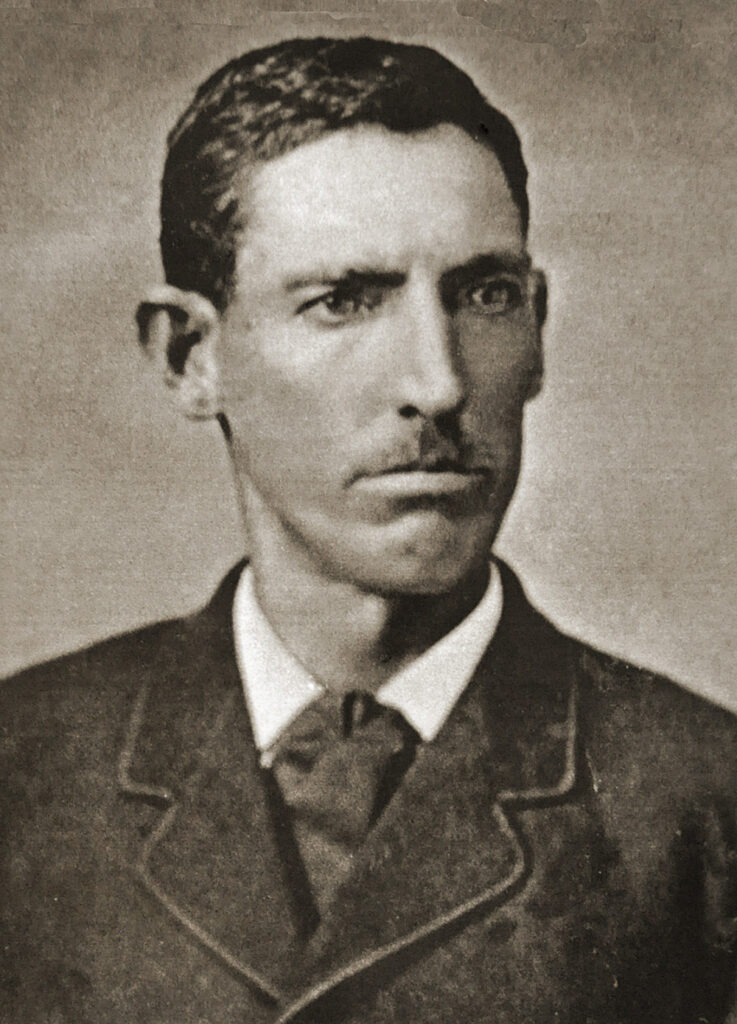

Within a month Colorado City recorded its first killing, not by an outsider, but by a trio of Texas Rangers. By most accounts cattleman William P. Patterson, the deceased, was a popular and likeable fellow—except when drunk. That January he’d lost by a single vote an election for sheriff of newly organized Mitchell County. His victorious rival was Texas Ranger Richard C. “Dick” Ware, a lawman involved in the 1878 fatal shooting of notorious train robber Sam Bass in Round Rock, Texas.

(Heart of West Texas Museum, Colorado City)

In the wake of his loss Patterson took to drink. During a binge that early May he shot up the town until Rangers disarmed and chained him to a mesquite tree, as Colorado City lacked a jail. Shortly after midnight on May 17 the recently freed Patterson started firing into the air outside the Nip & Tuck saloon. When a trio of patrolling Rangers—Corporal J.M. Sedberry and Privates Jeff Milton and L.B. Wells—investigated, they spotted Patterson and companion Ab Adair ambling down the street.

Confronting the pair, the Rangers asked who had done the shooting. Patterson pled ignorance. A dubious Corporal Sedberry demanded to check the cattleman’s pistol. “Damn you,” Patterson answered, “you will have to go examine somebody else’s pistol!” With a nod, Sedberry and rookie Ranger Wells moved to grab Patterson’s arms, but the muscled cowman broke free, yanked his pistol and fired at the corporal, who dodged the bullet but suffered powder burns. Before Patterson could fire again, Milton pulled his .45 and dropped him dead. The frightened and inexperienced Wells then shot the downed Patterson a second time as he lay on the street.

As word of the shooting spread, the crowd of cowmen at the bar inside the Nip & Tuck clamored for vengeance and the Rangers’ lynching—that is, until fearless Milton strode in with his Winchester leveled at the agitators.

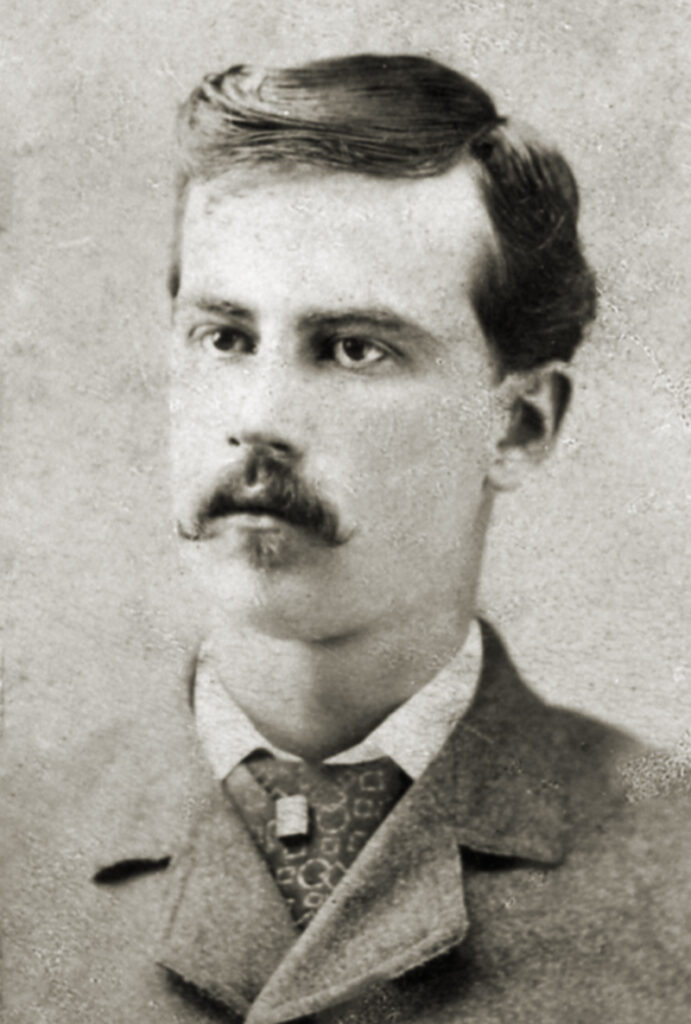

(Nita Stewart Haley Memorial Library, Midland)

When Sheriff Ware arrived, Sedberry, Milton and Wells turned themselves over to his custody, and tensions eased. Two days later Ware escorted the trio to their examining trial in the temporary courthouse. The justice set bond at $1,500, which local citizens sympathetic to the Rangers’ efforts to keep order soon provided. Though indicted for the killing, all three Rangers were exonerated two years later after a change of venue and a trial in Taylor County.

Deputy Sheriff Wayne B. Parks never received his day in court after a controversial 1885 shooting in Page & Charley’s saloon. That February 4 Ike and Joe Adair, sons of a prominent local cattleman, raised such a ruckus in the saloon’s gambling room that Deputy Parks had to step in to quell the commotion. The brothers took offense. Ike bolted from their table with gun in hand and aimed for Parks, who grabbed Ike’s arm. As they grappled, Joe opened his pocketknife, got behind Parks and slashed at the deputy’s head. Parks then yanked his pistol and blindly shot over his shoulder at the slasher while trying to keep his sibling from shooting. Joe collapsed to the floor with a bullet through his heart. The deputy continued wrestling with Ike until City Marshal Jim Woods arrived to disarm the gunman, ending the confrontation but not the rancor.

Though Parks was indicted for murder, animosity lingered for weeks among Adair’s family and friends. Three months later the deputy killed an inmate named Middleton during a May 3 escape attempt from the second-floor jail of the Mitchell County Courthouse. Middleton, an accused horse thief, jumped jailer T.J. Robinson, who was delivering supper to the prisoners. Hearing the commotion, Robinson’s wife dashed upstairs with a pistol and held off Middleton until Parks bounded up the steps to assist. When Middleton moved to resume his attack on the jailer, the deputy shot him through the head. A coroner’s jury ruled the killing justifiable.

Late on the evening of June 6 Parks was standing at the intersection of Oak and Second streets, speaking with friends, when an unknown assailant approached within 20 feet, took a potshot at Parks, then vanished in the night. Though Parks emerged unscathed, the deputy ran out of luck that October 29 following an opera house ball. After seeing his lady safely home around midnight, Parks started for his place, only to be shotgunned from ambush by someone in hiding. Parks dropped with 10 buckshot pellets in his neck and torso, living just long enough for neighbors to hear his moans.

Investigators found tracks and signs indicating one man had waited with two horses behind a tree while an accomplice—described by a Fort Worth newspaper as “some unknown fiend”—fired the fatal blast. Though suspicions fell on Adair family and friends, and authorities offered a $5,000 reward, Parks’ killers were never identified.

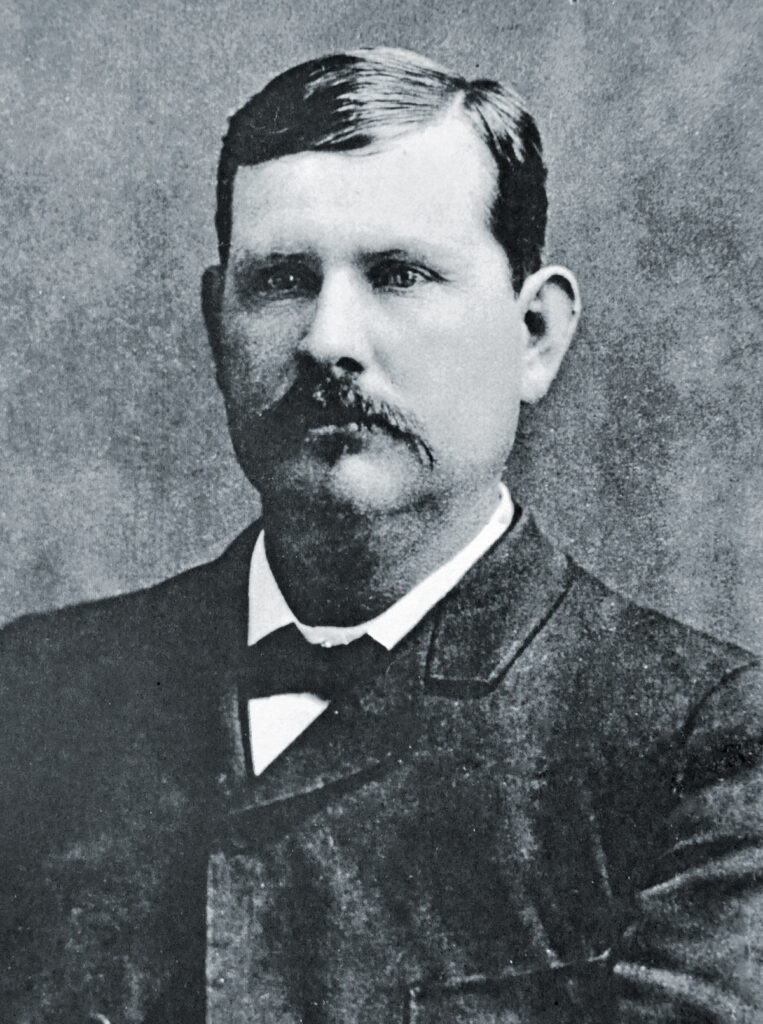

(Heart of West Texas Museum, Colorado City)

Parks was the second local lawman to have been killed that year. On May 28 gambler Ben Jacobs had shot and killed Deputy City Marshal W.B. “Black” Hardeman in a “variety bawdy house in the west end,” as one newspaper described the crime scene. “West end” was a euphemism for the town’s red-light and seedy saloon district. Details of the dispute between Hardeman and Jacobs remain murky, though news accounts reported Jacobs shot the deputy in the abdomen, left breast and face.

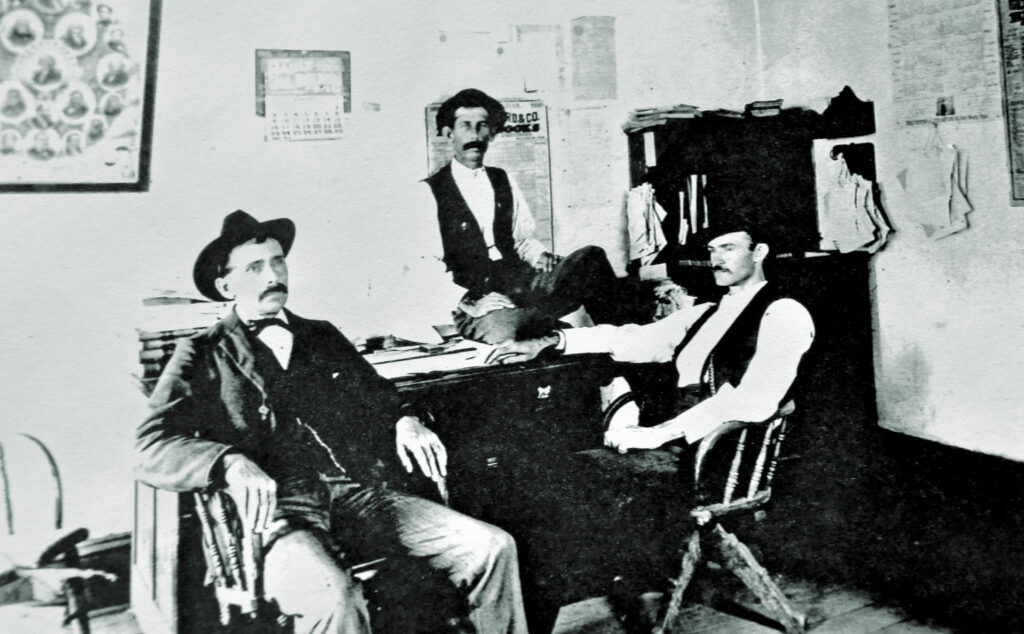

An “Arrangement” with the Law?

So common were Colorado City gunfights that one newspaper in 1884 flippantly detailed a minor encounter. “There was, as the ‘boys say,’ a six-shooter play made in the Favorite saloon on Oak Street last night, but nobody was hurt,” the reporter noted. “Officers and friends to the parties being near, the difference was soon adjusted.” Not all gunplay in town occurred in the west end. On May 28, 1886, a serious shooting broke out in a downtown photography gallery after one Amanda Bradley, described as “an inmate of a bagnio,” or brothel, threw a fit. Ordered to leave by proprietor F. Chapman, the woman departed and bitched about the insulting eviction to gambler Jack Martin, who strode to the studio to avenge the affront to the lady of questionable virtue. After the gallant Martin threatened Chapman, the photographer repaid Martin’s chivalry with a fatal blast from a shotgun that “filled his carcass with shot,” according to one news account, “and he went the way all such characters should go.”

(Preston Lewis Collection)

Colorado City’s police blotter recorded a variety of other violent incidents in the 1880s. Sheriff Ware held off a lynch mob intent on dispensing immediate justice to an accused child molester; a saloonkeeper attempted to murder a prominent businessman; a local resident shot his mistress before killing himself; an assailant with a sheep-shearing blade engaged in a “serious cutting affray” that left the victim with protruding entrails; and authorities discovered a mystery man with a fractured skull laid out in a freight car. T&P agent J.W. Ayers, who arrived in town in 1883, recalled no fewer than 16 fatal shootings on the city streets that decade.

Colorado City bloodshed received enough negative news coverage that the Sept. 1, 1883, edition of El Paso’s Daily Times reported, “We think that Colorado City is somewhat like a great many other western Texas towns—a good place to make money in, but rather a poor one, just yet, to carry a family to and make a home in.”

The violence might have been worse save for a rumored alliance between Sheriff Ware and west end kingpin “Uncle Archie” Johnson. Reportedly at the urging of the town fathers, Ware looked the other way regarding prostitution and illegal gambling, as long as the games remained square and visiting cowboys were not rolled, drugged, robbed, cheated or murdered. In return Johnson and cronies would tip off the law about potential breaches of the peace.

The arrangement between Ware and Johnson was important. Unlike the Kansas railheads, which cowhands might visit once a year after long drives, Colorado City expected and coveted the regular return business of cowboys. If crime got too far out of hand, ranchers might steer clear of town and trade elsewhere along the T&P.

One old-timer recounted an 1886 visit to Colorado City with his newly paid pals after their spring roundup. “We were all pretty well-heeled with cash,” he recalled, “but by the next morning there was not enough left in the whole outfit to buy a feed of oats for one of our horses. Old Archie and his gals had gotten it all, but nobody kicked.”

A Wealthy Hub

While Uncle Archie and company were liberating cowhands from their cash, Colorado City merchants and area ranchers also raked in money. For five years after the railroad’s arrival the town boomed, at one point claiming to be the busiest cattle shipping point in the nation. When the newly created Matador Cattle Co. marketed its first herd in 1881, drovers pushed the steers 110 miles south from Motley County to Colorado City. The 12-day drive earned the company an impressive $75 a head.

While outbound trains shipped cattle, sheep and wool out of Colorado City, inbound trains brought building supplies, ranching materials and consumer wares, which merchants distributed north and west for 200 or more miles. In the northwest corner of the Texas Panhandle the 3-million-acre XIT Ranch—which extended more than 200 miles south from the Oklahoma border in an irregular 30-mile-wide strip—split its purchases between the railhead in Colorado City, to the southeast, and the one in Trinidad, Colo., to the northwest. According to investor Amos Babcock of the Capitol Syndicate, which owned and operated the ranch, it was just over 100 miles from either railhead to the XIT. The distance mattered little. As the bookkeeper of a ranch headquartered 120 miles north of the railhead noted, “We had then to go to Colorado City for almost everything.”

Legendary Texas rancher Charles Goodnight ordered supplies from Colorado City for the 140,000-acre Quitaque Ranch he managed for Cornelia Adair in the Texas Panhandle. One 1882 freight receipt from merchant A.W. Dunn recorded a delivery of 334 spools of barbed wire, six kegs of fencing staples and 38 pieces of lumber. The 33,000-pound load was freighted at a rate of $1 per 100 pounds per 100 miles. Similar commercial transactions plus livestock sales made Colorado City a wealthy community.

(Heart of West Texas Museum, Colorado City)

Beyond supplying ranches with barbed wire, windmill equipment and necessities, Colorado City also provided emerging communities in west Texas and the South Plains with provisions and the most valuable commodity of all in the largely treeless country—lumber, an absolute essential for pioneers seeking to build homes and businesses and realize their dreams. Pioneering merchant George Singer, whose circa-1881 one-room store in Yellow House Canyon eventually spawned Lubbock, received his merchandise and mail from Colorado City, as did fledgling communities as far away as Tascosa, in the far northwestern corner of the panhandle.

In January 1883 Colorado City’s boom caught the eye of a St. Louis Globe-Democrat reporter who noted that the town’s business transactions for the prior year “amounted to about $10,000,000,” or more than $300 million in present-day dollars. A tenth of that income, reported the paper, went to town founder Dunn for his aggregate sales in merchandise and cattle.

The End of an Era

Anticipating a bright future, Colorado City in 1885 hosted a stockman’s ball to celebrate both the town’s prosperity and the opening of the new three-story brick St. James Hotel, complete with indoor plumbing. Cattlemen and their families from throughout Texas and New Mexico Territory attended the celebration. One contemporary young observer said of the ball, “They put the big pot in the little one.”

As impressive and ostentatious as the “pot” may have been, the celebration marked the end of Colorado City’s heyday, not its beginning. Multiple factors contributed to the subsequent rapid economic decline, including droughts, harsh winters, declining cattle prices and competing regional railroads, particularly those extending to Amarillo and San Angelo. Given multiple railheads from which to choose, west Texas ranchers weighed their options as closely as they weighed their steers. As the manager of the Spur Ranch in 1888 explained, “The advantage of a shipping point on the railroad depends not so much on its proximity to the ranch as on the condition of the range between here and there.”

Over the latter half of the 1880s Colorado City gradually declined in wealth, significance and, mercifully, violence. By 1890 the population had plummeted from its 1884 peak of 6,000 to 1,582, while several of the surrounding communities it had spawned surpassed it with their own rail stops and ambitions. Perhaps if Sheriff Ware and vice king Johnson hadn’t colluded to curb violence, Colorado City might have developed a more flamboyant reputation and ensured its place among the Old West’s famed cattle towns. Or maybe if Colorado City hadn’t been so convenient to the ranches it served—at least compared to Kansas cow towns—it would have birthed a trail herd or cowhand Herodotus to chronicle for posterity its brief time in the sun. Instead, Colorado City flamed out like a west Texas sunset, spectacular in its moment but soon replaced by other, more boisterous cow towns.

For further reading on this topic author Preston Lewis recommends If I Can Do It Horseback, by John Hendrix; Jeff Milton: A Good Man With a Gun, by J. Evetts Haley; and Lore and Legend: A Compilation of Documents Depicting the History of Colorado City and Mitchell County, compiled by J. Lee Jones Jr. and Nona C. Jones.

[ad_2]

Source link