Letters from the Sheridan Field Hospital

[ad_1]

A gloomy and tragic scene—one with which the inhabitants of the oft-contested city of Winchester, Va., were unfortunately all too familiar—unfolded throughout the night of September 19, 1864, as thousands of casualties from the Third Battle of Winchester were brought to makeshift hospitals throughout the community. “All the wounded,” reported Surgeon James T. Ghiselin, the Army of the Shenandoah’s medical director, were taken to “churches, public buildings, and such private dwellings as were suitable.”

It did not take long for Ghiselin to realize that the 40 structures transformed into ersatz hospitals would be insufficient to handle the army’s casualties, which exceeded 4,000 troops. Ghiselin also understood these spaces would be further strained with additional casualties as Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah pursued Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Confederates south toward Fisher’s Hill. Sheridan’s medical director quickly realized that the time had come to implement a plan, developed several weeks earlier, to transport hundreds of tents to Winchester and construct what would be known as the Sheridan Field Hospital—the largest hospital of its kind constructed during the Civil War.

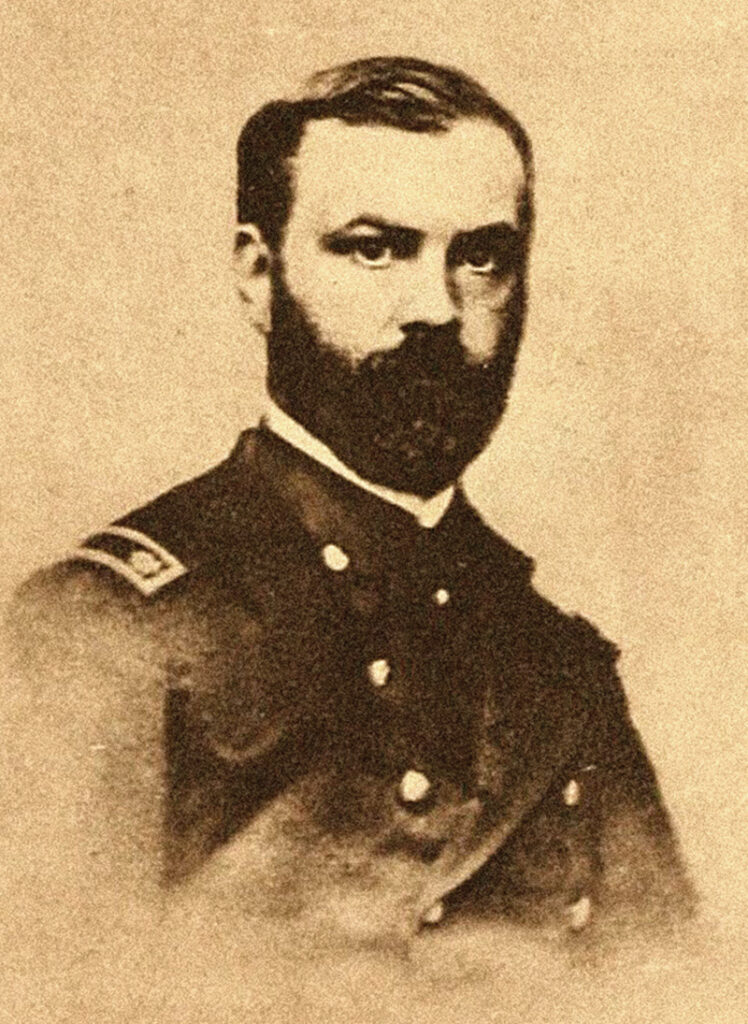

(Library of Congress)

The day after the battle Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes ordered Surgeon John Brinton “to proceed without delay to Winchester” and supervise the construction of “a large tent hospital…to be of a capacity of four to five thousand beds.” The following night Brinton arrived in Winchester. While erecting “500 tents…was no slight matter,” as Brinton asserted, the task of erecting the Sheridan Field Hospital was completed on September 29, 1864, with the support of approximately 500 troops from Colonel Oliver Edwards’ brigade. After the hospital’s construction, and in the ensuing weeks, a bevy of civilians, including relief agents from the U.S. Christian Commission and nurses arrived to aid in caring for the wounded. Among them was Jane Boswell Moore.

Moore, a native of Baltimore, Md., who at the war’s outset aided wounded and sick Union soldiers brought to the city, believed that by the late summer of 1862 her talents could be put to better use in the field. After the conflict’s bloodiest day at Antietam, Moore ventured from Baltimore to Sharpsburg. From that moment until the war’s end, she cared for wounded soldiers in the aftermath of the some of the conflict’s fiercest engagements in the East, including Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and Petersburg.

In the autumn of 1864, Moore came to Winchester. During that time Moore aided wounded soldiers in various hospitals throughout the town, including the Sheridan Field Hospital. As had been the case throughout her service, Moore took a special interest in particular soldiers and decided to share their stories and her experiences by sending letters to “a number of religious and secular periodicals.” Moore hoped that publication of these letters would encourage donations of supplies. While difficult to quantify the amount of donations Moore secured, a Congressional report noted decades after the conflict that her published letters prompted “great quantities of donations.”

During Moore’s stint in Winchester, two of her letters appeared in the Advocate and Family Guardian—a biweekly newspaper published by the American Female Guardian Society in New York City. These letters, printed in early 1865, reveal much about a nurse’s experiences caring for soldiers wounded during Phil Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Campaign, illuminate the sufferings of the wounded, and serve as a powerful reminder of war’s devastating and tragic consequences.

(Library of Congress)

Moore’s first letter, published on January 16, 1865, includes an account of her encounter with Sophronia Loder, a mother who ventured to Winchester from Indiana when she learned that her son, Sergeant Adam Loder, 18th Indiana Infantry, had been wounded at the Battle of Fisher’s Hill on September 22. Unfortunately, the wounds Sergeant Loder received to his left lung and left arm proved mortal. He died on October 7, 1864, prior to his mother’s arrival. In addition, Moore recounts the difficulties experienced by Private Walter F. Reed, shot in the jaw at the Battle of Cedar Creek, and Corporal Isaac Price, 15th West Virginia Infantry, who lost both arms in the skirmish near Hupp’s Hill, south of Cedar Creek, on October 13, 1864.

Advocate and Family Guardian

January 16, 1865

I rose from a rude bed on the floor of a house in Braddock Street, in the old town of Winchester, Va., where we have spent seven weeks ministering to the wounded in the last great battle [Cedar Creek]….At eight o’clock daily, an ambulance reports for duty… we, away from the home, and standing in the stead of kindred, dedicate this day, by an act of respect, to the dead, who sleep in Virginia soil….On this bright morning, we pluck a sprig of evergreen to send to the loved ones far away from the grave in which their son and brother is sleeping, and our hearts are saddened to think how these mounds are filling loving hearts with anguish and desolation….Every one of these small shingle-boards, with its miserable and almost illegible penciling, has its history, and that of some is heartrending. Shall I briefly allude to those whose names were carved by same hand?

In this corner lies Sergt. Loder, from Indiana; seven weeks ago, in the ambulance in which we rode from Martinsburg here, we met his mother, and to know her was to love her. In the pages of memory the record of those pleasant hours and interesting conversation will remain, when years have passed away. It is not often you can know the heart of a stranger, yet sometimes, in our journey through life, we meet a gentle, loving spirit whose sympathies with our own, and whose transparency and simplicity of character are as rare as charming. Sad, indeed, was the result that widowed mother’s journey, for ere she left home her son was laid in this burial spot. She waited long, in hopes of taking him to his wife and child, but this, owing to the manner of his burial, was not accomplished; and she returned, leaving us to mark the spot; and on the very day I performed this duty, I received from her one of those warm, affectionate letters that proved ours to be more than common acquaintanceship….Our sad task over, we load the ambulance with soft crackers, pickles, wine, condensed milk, tobacco (needed in the terribly offensive state of wounds), tomatoes, jelly, butter, and eggs, (when they can be obtained). Bay rum, soap, canned fruits, stationery, clothing, &c., and drive over a rough road, up the hill to Sheridan’s field hospital, where snowy tents loom up against the exquisite hue of the peaks of the distant Blue Ridge—tents alas! so full of misery. Here, Wards, three, four, five, six, seven, ten, twelve, fifteen, sixteen, nineteen, eighteen, twenty, twenty-six and seven, and the gangrene tents claim our special attention.

Let us hurriedly glance at some of the more interesting cases. In ward three Walter F. Weed, of the 114th N.Y.V., has long been a candidate for soft food, his mouth and jaw being terribly broken by a minie ball. At first he could not speak, and we brought him fresh milk; but now he is able to tell his wants, chew a little, and is going home. His can of peaches we find he has been saving to eat on the way, so we add other articles, and smile at his provident forethought….Isaac Price of the 15th loyal Va., looks dispirited, as he sits with both arms gone. Perhaps he is thinking of the wife, mother, and nine children at home on whom as well as himself this heavy trial has fallen…

Well, reader, no doubt you are weary of so much suffering, and so also are we, so we hurry home at half-past twelve, making a very plain and hasty dinner of crackers, beef and as it is Thanksgiving, some canned tomatoes…and then drive to the “front,” with dried fruits, condensed milk, crackers, stationery, needle-bags, little books and papers. We have paid constant attention to other regiments and to-day we will remember Maryland. It is quite disappointing to find the members of the 6th mostly on picket, but amongst those left in camp our stock is decidedly unpopular…

We pay a visit to the poor soldiers in Camp Convalescent, and they look so sadly into the ambulance, it makes one’s heart ache. After tea, a sick New Yorker sends for something he can eat; so we put crackers, butter, a lemon, loaf sugar and calves-foot jelly on a tin plate, and send to him. At night there are letters to write for the sick, and a head-board to carve for the dead—sad, yet needless duties; and, as I look to remember that not to me has the day passed without bringing its own sad memories.

One month after Moore’s first letter appeared in the Advocate and Family Guardian, the paper published a second. In addition to describing the grisly scenes that followed the Battle of Cedar Creek, Moore shared the experiences of Private George Hill, 13th West Virginia, who lost his right leg at Cedar Creek, and his interactions with Carrie Fahnestock, the seven-year-old daughter of Gettysburg, Pa., merchant Edward Fahenstock, who sent a brief note and housewife to the U.S. Christian Commission to hopefully brighten the spirits of a wounded Union soldier. In addition to including the text of Fahnestock’s letter, Moore also sent Hill’s response to it. Hill survived his wound but perished 14 years later at the age of 32. Whether Hill’s war wound contributed to his death is unknown.

Advocate and Family Guardian

February 16, 1865

On the twenty-first of October, after the last great battle in the valley, Dr. [James H.] Manown, the kind-hearted surgeon of the fourteenth West Virginia, told me that towards evening a number of wagons would arrive from the “front,” with wounded, on their way to Martinsburg, twenty-two miles further. My orderly was sent to borrow pails, and we were soon busily employed making milk punch. Just about dark, an immense double train of rough army wagons arrived, blocking up the streets, and belonging to the Sixth, Eighth, and Nineteenth Corps, each freighted with mangled, bleeding, yet precious burdens, among whom our work commenced. It was a strange, warlike scene—dark night settling over Virginia roads, mud, cavalry, and wagons, whilst with flaming candles (lanterns were not be to procured) we supplied the wounded in the different wagons, giving to each half a tin cup full, and to others hot tea. The night was raw and chilly, and both then and on the next, our duties being the same, many suffered from the cold, especially the rebels whose clothes were ragged and thread-bare, many having old quilts and spreads around their shivering forms. They were mostly from North and South Carolina, Louisiana, Virginia, Georgia, &c., ours from West Va., N.Y., Mass., Ohio, Ind., Pa., &c, &c. Many had to be lifted up to drink, and two were beyond the reach of all earthly pain. Two whose legs had been amputated, one from N.Y. the other from Pa. implored me to have them left in Winchester, they being unable to endure the rough ride over stony roads, in lumbering wagons, and Dr. Manown had them taken out, with others, for whom a further ride would have been impracticable. Among them was Georgie Hill, who was fearful of being moved lest the stump of his right leg should be jarred, so Dr. M. lifted him tenderly in his arms, and carried him into his own hospital, in the Southern Methodist Church, on Braddock Street, two doors from our quarters…lying in front of the pulpit, I found him. He did not look more than twelve years old, his skin was fair as a girl’s, his hair dark, and his great black eyes, just about as large and full of mischief as any I ever saw. Though I had a great many serious cases in Sheridan Hospital, who were not nearly so well cared for, I generally managed at noon to get a minute to take a can of peaches or cherries, or some other delicacy to the dear little fellow, whose bright eyes sparkled with pleasure…

(Universal History Archive (Getty Images))

One day I thought of a present for Georgie, sent by a little girl in Gettysburg to the Christian Commission, and entrusted to me. It was a needle-book or housewife, made of pretty red, white, and blue merino, or soft flannel, with pins, black-thread, a nice letter, some little bits of candy wrapped in paper, and a sweet carte-de-visite of a dear little girl. So I told Georgie about it, and his face lighted up as he said, “Bring it right in, so that I can see it.” Some days elapsed before I found time to do so, receiving at length a gentle reminder that, “that though promised three days before, he had not seen it yet.” So at noon I hurried into the church, and stooping on the floor, showed Georgie the wonderful contents of the needle-book, and read to him little Carrie’s letter. “Isn’t she a little one!” he exclaimed, his eyes expanding to their utmost capacity. This is Carrie’s letter:

Gettysburg, February 25th [1864]

Dear Soldier,—I can’t do much for you, as I am a very little girl—but I think of you, and pray for you too. I hope you are good, and pray for yourself. When we had the battle here, I saw how you had to suffer, and I pity you. I carried things to sick soldiers, and if you were here would do it for you. I send you my picture that you may see how small I am.

Good-by. Carrie Fahnestock.

A few days after, I went in to give eggnog to the wounded, and was sorry to see Georgie about to be taken in an ambulance from the church to Sheridan field-hospital. His few worldly possessions lay on his stretcher, and he looked sorry to leave, for it was one of the coldest days we had had. I tried to comfort him, telling him I daily visited Sheridan hospital, and all he had to do in case we did not find him among so many was to let us know the number of his tent. “How can I let you know?” was his doubtful reply. But late in the afternoon, I sent James with some little article for poor Jones, in whom I took a deep interest, and sure enough in “Ward Seven” lay Georgie…

The next day was intensely cold. The sky was strangely covered with bright, shifting clouds, looking like grotesquely-shaped precipices, the exquisitely-tinted hills of the Blue Ridge forming a framework or border to the picture of the hillside, with its orchard of ruined fruit-trees, through which numberless teams and wagons wended their way to the closely-gathered tents of Sheridan, covering so many suffering and dying souls… I sought out Georgie, and wrote in answer to Carrie’s letter:

Sheridan Hospital, Ward 7

Nov. 5th 1864 Winchester, VA

Dear Little Carrie,—I am quite a little boy, and my name is Georgie Hill, Co. K, 13th West Va. Regiment. I have been a little soldier boy fourteen months, and was wounded in the leg on the nineteenth of October near Cedar Creek, Va., with a minnie ball. I was carried to Newtown and lay in a tent, and on the twentieth the doctor took my right leg off. My father is dead, but I have a mother, three brothers and one sister, and my home is in Mason County, Va. Three of my brothers are dead, all soldiers, one died in the Mexican war, one at the siege of Vicksburg, and one in the hospital in Gallipolis, Ohio….Miss Moore gave me your dear little picture and present. She told me I must keep it as long as I live to remember the time I lay on the church floor in Winchester, after the battle; and I will. Yesterday they brought me to this field- hospital, where all the sick are in tents, and I find mine very cold this windy day. I don’t like it as well as a house, and if I could have stayed, would not have left the warm church [Southern Methodist Church on Braddock Street]. Miss Moore found me to-day right in her ward—she brought me a little puzzle-box, with seven pieces of wood, and if you know how, you can make squares and funny figures. At first I could not put them all back in the box. I am going to play with it when I go home, before I get my wooden leg and am able to run around. I have not been home for fourteen months, and I don’t know when I shall get there. I have not had a letter for two months either, my mother does not get my letters, or I don’t get hers, I don’t know which. I am going to eat candy after dinner, (this arrangement was not made with difficulty) I have had some pudding, brought in by a Winchester lady, but it has lemon in it, and I don’t like lemon, so I keep looking at the candy. Miss Moore asks if there is anything else I want to say, but I never wrote to you before, so you must excuse me. Good-by, Carrie.

Your little friend, Georgie Hill

(Library of Congress)

The Sheridan Field Hospital officially closed on January 4, 1865. Whether Moore departed Winchester before or after that date is unclear. Evidence indicates Moore was with Union forces in Richmond at war’s end. Four years of nursing wounded soldiers in hospital and on the battlefield exacted a physical toll on Moore. In 1888, suffering from “extremely poor health, caused by her army service,” the Federal Government awarded Moore a monthly pension of $50.

After the conflict Moore, who married Jacob Bristor, a veteran of the 12th West Virginia Infantry in 1867, committed herself to aiding the less fortunate at home and abroad. At the time of her death in 1916 The Baltimore Sun reported she contributed “about $150,000 to the foreign and domestic missionary societies of the Presbyterian Church, most of these gifts having been made in the form of property and ground rents in Baltimore.”

Jonathan A. Noyalas is director of Shenandoah University’s McCormick Civil War Institute and the author or editor of 15 books.

[ad_2]

Source link