A Jungian Field Guide to Finding Meaning and Transformation in Midlife – The Marginalian

[ad_1]

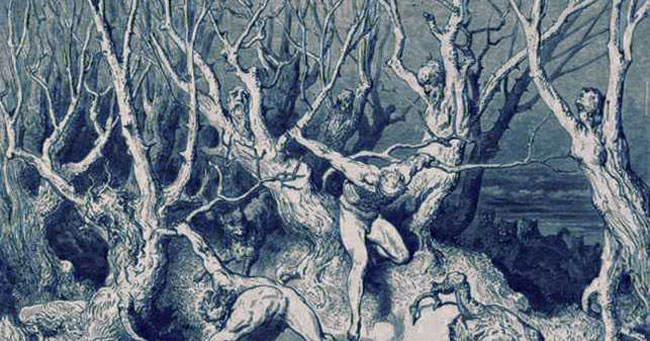

“In the middle of the journey of our life I found myself within a dark woods where the straight way was lost,” Dante wrote in the Inferno. “The perilous time for the most highly gifted is not youth,” the visionary Elizabeth Peabody cautioned half a millennium later as she considered the art of self-renewal, “the perilous season is middle age.”

In The Middle Passage: From Misery to Meaning in Midlife (public library), Jungian analyst James Hollis offers a torch for turning the perilous darkness of the middle into a pyre of profound transformation — an opportunity, both beautiful and terrifying, to reimagine the patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior acquired in the course of adapting to life’s traumas and demands, and finally inhabit the authentic self beneath the costume of this provisional personality.

One has entered the Middle Passage when the demands of the true self press restive and uprising against the acquired persona, eventually colliding to produce untenable psychic ache — a “fearsome clash,” Hollis writes, leaving one “radically stunned into consciousness.” A generation after James Baldwin contemplated how myriad chance events infuse our lives with the illusion of choice, Hollis considers our unexamined conditioning as a root cause of this clash:

Perhaps the first step in making the Middle Passage meaningful is to acknowledge the partiality of the lens we were given by family and culture, and through which we have made our choices and suffered their consequences. If we had been born of another time and place, to different parents who held different values, we would have had an entirely different lens. The lens we received generated a conditional life, which represents not who we are but how we were conditioned to see life and make choices… We succumb to the belief that the way we have grown to see the world is the only way to see it, the right way to see it, and we seldom suspect the conditioned nature of our perception.

Haunting this conditional life are our psychic reflexes — the coping mechanisms developed for the traumas of childhood, which Hollis divides into two basic categories: “the experience of neglect or abandonment” or “the experience of being overwhelmed by life,” each with its particular prognosis. The overwhelmed child may become a passive and accommodating adult prone to codependence, while the abandoned child may spend a lifetime in addictive patterns of attachment searching for a steadfast Other. These unconscious responses adopted by the inner child coalesce into a provisional adult personality still preoccupied with solving the emotional urgencies of early life. Hollis observes:

We all live out, unconsciously, reflexes assembled from the past.

Carl Jung termed such reflexes personal complexes — largely unconscious and emotionally charged reactions operating autonomously. Most of life’s suffering stems from the unexamined workings of these complexes and the conditioned choices they lead us to, which further sever us from our true nature. Hollis writes:

Most of the sense of crisis in midlife is occasioned by the pain of that split. The disparity between the inner sense of self and the acquired personality becomes so great that the suffering can no longer be suppressed or compensated… The person continues to operate out of the old attitudes and strategies, but they are no longer effective. Symptoms of midlife distress are in fact to be welcomed, for they represent not only an instinctually grounded self underneath the acquired personality but a powerful imperative for renewal… In effect, the person one has been is to be replaced by the person to be. The first must die… Such death and rebirth is not an end in itself; it is a passage. It is necessary to go through the Middle Passage to more clearly achieve one’s potential and to earn the vitality and wisdom of mature aging. Thus, the Middle Passage represents a summons from within to move from the provisional life to true adulthood, from the false self to authenticity.

The summons often begins with a call to humility — having failed to bend the universe to our will the way the young imagine they can, we come to recognize our limitations, to confront our disenchantment, to reckon with the collapse of projections and the crushing of hopes. But this reckoning, when conducted with candor and self-compassion, can reward with “the restoration of the person to a humble but dignified relationship to the universe.”

This, Hollis argues, requires shedding the acquired personality of what he terms “first adulthood” — the period from ages twelve to roughly forty, on the other side of which lies the second adulthood of authenticity. Bridging the abyss between the two is the Middle Passage. He writes:

The second adulthood… is only attainable when the provisional identities have been discarded and the false self has died. The pain of such loss may be compensated by the rewards of the new life which follows, but the person in the midst of the Middle Passage may only feel the dying… The good news which follows the death of the first adulthood is that one may reclaim one’s life. There is a second shot at what was left behind in the pristine moments of childhood.

Hollis envisions these shifting identities as a change of axes, moving from the parent-child axis of early life to the ego-world axis of young adulthood to the ego-Self axis of the Middle Passage — a time when “the humbled ego begins the dialogue with the Self.” On the other side of it lies the final axis: “Self-God” or “Self-Cosmos,” embodying philosopher Martin Buber’s recognition that “we live our lives inscrutably included within the streaming mutual life of the universe” — the kind of orientation that led Whitman, who lived with uncommon authenticity and made of it an art, to call himself a “kosmos,” using the spelling Alexander von Humboldt used to denote the interconnectedness of the universe reflected in his pioneering insistence that “in this great chain of causes and effects, no single fact can be considered in isolation.” The fourth axis is precisely this recognition of the Self as a microcosm of the universe — an antidote to the sense of insignificance, alienation, and temporality that void life of meaning. Hollis writes:

This axis is framed by the cosmic mystery which transcends the mystery of individual incarnation. Without some relationship to the cosmic drama, we are constrained to lives of transience, superficiality and aridity. Since the culture most of us have inherited offers little mythic mediation for the placement of self in a larger context, it is all the more imperative that the individual enlarge his or her vision.

These shifting axes are marked by several “sea-changes of the soul,” the most important of which is the withdrawal of projections — those mental figments that “embody what is unclaimed or unknown within ourselves,” born of the tendency to superimpose the unconscious on external objects, nowhere more pronounced than in love: What is so often mistaken for love of another is a projection of the unloved parts of oneself.

Drawing on the work of Jungian psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz, Hollis describes the five stages of projection — a framework strikingly similar to the seven stages of falling in and out of love that Stendhal outlined two centuries ago. Hollis writes:

First, the person is convinced that the inner (that is, unconscious) experience is truly outer. Second, there is a gradual recognition of the discrepancy between the reality and the projected image… Third, one is required to acknowledge this discrepancy. Fourth, one is driven to conclude one was somehow in error originally. And, fifth, one must search for the origin of the projection energy within oneself. This last stage, the search for the meaning of the projection, always involves a search for a greater knowledge of oneself.

In consonance with Joan Didion’s piercing insistence that “the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life is the source from which self-respect springs,” Hollis considers the ultimate payoff of this painful turn from illusion to disillusionment:

The loss of hope that the outer will save us occasions the possibility that we shall have to save ourselves… Life has a way of dissolving projections and one must, amid the disappointment and desolation, begin to take on the responsibility for one’s own life… Only when one has acknowledged the deflation of the hopes and expectations of childhood and accepted direct responsibility for finding meaning for oneself, can the second adulthood begin.

The vast majority of our adult neuroses — a somewhat dated term, coined by a Scottish physician in the late eighteenth century and defined by Carl Jung as “suffering which has not discovered its meaning,” then redefined by Hollis as a “protest of the psyche” against “the split between our nature and our acculturation,” between “what we are and what we are meant to be” — arise from the refusal to acknowledge and let go of projections, for they sustain the persona that protects the person and keep us from turning inward to befriend the untended parts of ourselves, which in turn warp our capacity for intimacy with others. Hollis writes:

We learn through the deflation of the persona world that we have lived provisionally; the integration of inner truths, joyful or unpleasant, is necessary to bring new life and the restoration of purpose.

[…]

The truth about intimate relationships is that they can never be any better than our relationship with ourselves. How we are related to ourselves determines not only the choice of the Other but the quality of the relationship… All relationships… are symptomatic of the state of our inner life, and no relationship can be any better than our relationship to our own unconscious.

It is only when projection falls away that we can truly see the other as they are and not as our need incarnate, as a sovereign soul and not as a designated savior; only then can we live into Iris Murdoch’s splendid definition of love as “the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real,” and be enriched rather than enraged by this otherness.

Defying the dangerous Romantic ideal of love as the fusion of two souls and echoing Mary Oliver’s tender wisdom on how differences make couples stronger, Hollis writes:

When one has let go of the projections and the great hidden agenda, then one can be enlarged by the otherness of the partner. One plus one does not equal One, as in the fusion model; it equals three — the two as separate beings whose relationship forms a third which obliges them to stretch beyond their individual limitations. Moreover, by relinquishing projections and placing the emphasis on inner growth, one begins to encounter the immensity of one’s own soul. The Other helps us expand the possibilities of the psyche.

[…]

Loving the otherness of the partner is a transcendent event, for one enters the true mystery of relationship in which one is taken to the third place — not you plus me, but we who are more than ourselves with each other.

Ultimately, healthy love requires that we cease expecting of the other what we ought to expect of ourselves. In so returning to ourselves from the realm of projection, we are tasked with finally mapping and traversing the inner landscape of the psyche, with all its treacherous terrain and hidden abysses. Hollis writes:

It takes courage to face one’s emotional states directly and to dialogue with them. But therein lies the key to personal integrity. In the swamplands of the soul there is meaning and the call to enlarge consciousness. To take this on is the greatest responsibility in life… And when we do, the terror is compensated by meaning, by dignity, by purpose.

[…]

Our task at midlife is to be strong enough to relinquish the ego-urgencies of the first half and open ourselves to a greater wonder.

In the remainder of The Middle Passage, Hollis goes on to illustrate these concepts with case studies from literature — from Goethe’s Faust to Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground to Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” — illuminating how personal complexes and projections play out in everything from parenting to creative practice to love, and how their painful renunciation swings open a portal to the deepest and most redemptive transformation. Complement it with Alain de Botton on the importance of breakdowns and Judith Viorst on the art of letting go, then revisit Ursula K. Le Guin’s magnificent meditation on menopause as rebirth.

[ad_2]

Source link